Story

Introduction to THE HOLY GHOST STORY

Why the Holy Ghost? The roots of American folk music has been described as a trinity in which Pete Seeger is the father, Bob Dylan, the son, and my father, Bob Gibson is the Holy Ghost of Folk.

Bob Gibson was a devilishly charismatic choirboy in the midst of the fray as folk music was wrestled from the historical purists and redeemed as a popular art form. He was one of the redeemers. His repertoire and his life story reflect the contest between light and dark.

The gospel of “Good News”, “Joy Joy” and “You Can Tell The World” commingles with the unrepentant “Farewell, My Honey, Cindy Jane” and “Baby, I’m Gone Again”.

He rose to nearly mythic fame then fell from grace. His years of addiction and eventual recovery are woven through his songs. From humorously confessional songs like “Box of Candy and a Piece of Fruit” “Just A Thing I Do” “Mendocino Desperados” and “Looking For The You” to an anthem of sobriety “Pilgrim,” Gibson transformed his darkest days into light and humor.

Although the “Holy Ghost” reference may be taken with a grain a salt, there is some truth to it. I, for one, am haunted by my father’s music. This website is not just an archive, it is a monument carved in pixels, an appreciation of an enduring body of music and the man who made it.

Meridian Green

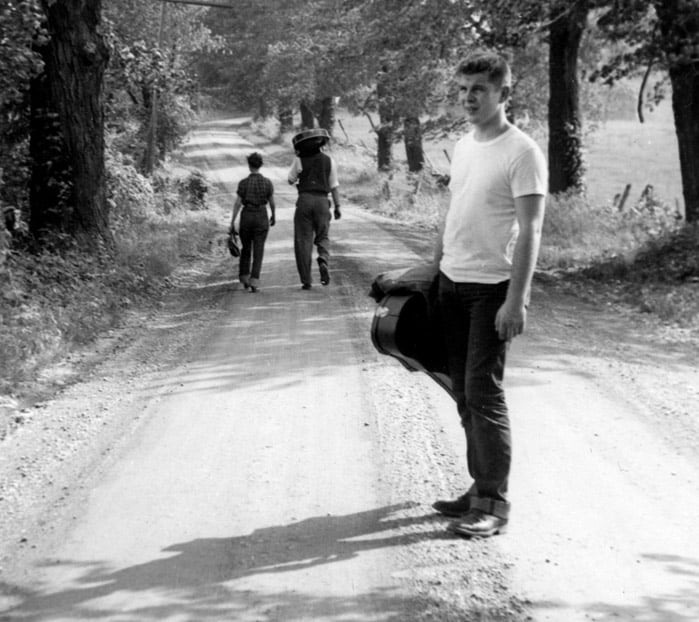

Visiting Pete Seeger in 1953

Pete Seeger Welcoming Visitors

In his autobiography, I Come For To Sing, Bob begins his story with meeting Pete Seeger in 1953. He and his friend, Dick Miller, went to interview Pete for a New Yorker article.

Laying Hands On Pete’s Banjo

“I never got to know Pete Seeger well, but he had a profound influence on my life. It was 1953 and the day I met him was really the day I began.

After spending an afternoon helping Pete build a chimney, listening to stories about Bill Broonzy and Woody Guthrie, Toshi made a wok full of vegetables for supper.”

On the Road to Becoming a Folksinger

“After the meal, it was quiet… kind of holy. I don’t use that word lightly…

Pete stepped inside the house, took this long necked banjo off the log wall and played Leather Wing Bat and some other songs.

By the time the evening was over, I knew I was going to get a banjo. The setting and the man already captivated me, but when he played the banjo, it blew me away. It changed my life.

IT CHANGED MY LIFE!”

The Young Bob Gibson - Before He Became A Folksinger

Bob & Rose Gibson Marry in 1952

Before the fateful day when Bob Gibson met Pete Seeger, he was a newly wed and an up-and-coming, suit-wearing salesman of a speed reading program who’d just been featured in the Harvard Business Review. Things were going so well for Bob, it’s hard to know why Rose’s foster mother wept for a week after the wedding which she did NOT attend.

A Lobster Fisherman in 1949

He’d already sown some wild oats hitching-hiking around the country. He was, for a brief while, a lettuce packer, a short-order cook, and then spent a summer as a lobster fisherman in Maine. He joined the Merchant Marine to stay out of the army until he found out the rheumatic fever he had as a child had left him with a heart murmur making him 4-F.

The Jukebox

“In the spring of 1949, Bob Gibson began to come over and add his voice to those of the neighbors. He received the nickname “the Jukebox” because he’d play for hours, never stopping, even when the gloom was as thick as a cup of Italian coffee. He sang with a voice which was golden like the guitar chords themselves.”

Bob Gibson (Nov. 16, 1931 to Sept. 28, 1996)

Bob grew up along the Hudson River, born in Brooklyn, raised in Tuckahoe, then Tompkins Corners. His father, Samuel, opted out of radio to become a chemical engineer with a two hour commute to and from work that left little time at home with the family. Bob said of his mother, Annabelle, “She was a weird woman. I was very distant from her.”

“When I was in school I was involved in everything musical- mixed chorus, a cappella chorus, and marching band. I played the lead in a community theater production of Down in the Valley and sang in church thanks to an inspiring choir director, Don Rock.

Bob and his brother Jim are confirmed.

But I was totally divorced from Catholicism. These guys wore funny clothes and they dedicated their lives to knowing this [mystical stuff] and yet they wouldn’t tell me. The first song I ever wrote was an anti-Catholic diatribe about plenary indulgences. Even as a kid I knew it was corrupt.”

Bob, sister Anne, and brother Jim in 1941

“I was deemed incorrigible by the school board and sent to parochial school in the city. They figured a year at the Irish-Christian Brothers would straighten me out. I learned that when you lived that far out, they didn’t bother to call if you didn’t show up.

I’d get on the express train to Times Square where there were movies all day. That’s probably the source of most of my education about history, relationships, the fundamentals of life… I learned it all at the movies.”

Sing For The Song 1954 to 1958

Bob and Rose in Washington Square

“I started hanging out at Washington Square. There was a good scene there, a conclave. At the time the interest everywhere was in traditional music, and I had great respect for the tradition- for the music. I wasn’t a purist though, because those ballads go on and on.”

“I got involved in a wonderful project, trying to track down people still alive in one family — three different generations— who still sang songs that they’d learned from their grandmother. The point was to try to tell whether changes in the song were done consciously or accidentally. A lot of those traditional songs [were passed along by] the grandmother while the grandchildren dried the dishes or sat on the front porch swapping songs. There was no time limitation.”

Collecting Folksongs of Ohio

“The Shaker Heights Women’s Club decided to pay me $50 to sing some songs… I would have been delighted just to sing. I was, at that time, busy looking for an audience. I was the person who took the banjo out at the beginning of the party and was the last person there. Later I identified that type and said “Aha! I was one of those, wasn’t I?” But I carried on with incredible, boundless — just boundless — enthusiasm.”

Taking Liberties

“When you’re singing in a saloon and people are coming in, paying a couple of bucks to forget their lives of quiet desperation, you don’t have the same kind of freedoms, you’ve got to communicate something to them. I began to rewrite the songs to work better for the audience I was singing for. .”

“There were those who said, “That ain’t the way you do it. You have a pure artifact here and you gotta leave it.” One could be a purist and some chose to do that. I was taking a lot of liberties with the music because I was looking to introduce people to folk music as an entertainment medium. Of course, this upset the true folkies, but the thing was, I was working and they weren’t!”

“I came up with songs that became very important in the folk music thing. All My Trials, Lord, Soon Be Over was on Offbeat Folksongs and was recorded by many others. The first recording of Michael, Row the Boat Ashore was on Carnegie Concert. Pete Seeger and I’d both learned it from Tony Saletan. Three years after I recorded it, it supposedly was “written” by one of the Highwaymen — but that’s the folk music business!”

Taking The Stage

“The Arthur Godfrey Show was a real biggie for me. I competed in the Arthur Godfrey Talent Scouts show in 1957. I played Andalucian Dance, a banjo tune that I had put together. I won the competition and became a regular on his show.”

“We played together on the show. I had the banjo and he played the baritone ukelele, so it was perfect. I‘d go to New York, work at the Blue Angel at night and his show in the morning. It was big time. One day I fell asleep on the Godfrey show. He thought it was funny—thank God!

Bob Gibson’s incandescent performances launched new coffeehouse and cabaret “listening rooms” in Chicago, New York City and around the country. Those nightclubs helped foment the great folk ferment. By 1959, Bob had recorded four albums for Riverside, two albums for Elektra, appeared on the Arthur Godfrey radio and TV show, played at the Gate of Horn for nearly a year, all while performing at clubs across the country. By 1959, he also had four children, three daughters with wife Rose, and a son with Jovita who soon married Bob Camp.

Gate of Horn - 1956 to 1961

Studs Terkel on Bob at the Gate of Horn:

“ People say memories deceive— memories don’t! Memories italicize … And to me the memory is 1956. Al Grossman opened the Gate of Horn… It didn’t work those first two weeks. In the third week appears a young guy with a crew cut, an infectious grin, and a banjo on his chest. When the kid first appeared, I thought, “Another one!” There had been so many kids cloning Pete or Woody. But when he began to sing out — that’s what he did — I knew he was special… Suddenly the place was electricity. From that moment on, the electricity of Bob Gibson caught on. It was the excitement of Bob’s performance that spread the word… It was Bob, the house artist who, more than any other performer, established the Gate of Horn and Chicago as a citadel of folk music in the country, and Bob’s role was that of a troubadour of ancient days, but of now.”

Grossman’s Citadel of Folk

Just as Bob Gibson was on the cutting edge so was his manager, Albert Grossman, equally ahead of his time. Grossman created the Gate of Horn in Chicago, the first citadel of the new folk music, where he presented Bob Gibson, Gibson & Camp, Glenn Yarbrough, Odetta, Joan Baez, Judy Collins and others. Grossman co-founded the Newport Folk Festival in 1959. His music management clients included Bob Gibson, Peter Paul & Mary, Bob Dylan, Phil Ochs, Richie Havens and Janis Joplin.

Newport Folk Festival 1959

“Joan Baez sang with me at the Gate of Horn. It very exciting. Then there was the Newport Folk Festival! Co-producer, George Wein, had told me and everyone else who was on the bill not to add anyone, but after singing a few songs, I brought Joan onstage. I knew I could get away with it. It was magical! People have tended to make a big deal of this, but I never have known why. It was like ‘discovering’ the Grand Canyon. Someone was bound to notice it was there!”

Virgin Mary Had One Song (Two)

“I spent two weeks at The Gate of Horn baffled, flattered and terrified by what appeared to be dazzling success just within reach. Within me the demons engaged in a riotous dance, coaxing me with the soft light, the maleness around me, the overt sexuality that erupted as inhibitions were anesthetized by alcohol. I knew only that at age 18, I was not cut out for the cocktail crowd. I needed my academic, rebellious, coffee-drinking admirers who listened single-mindedly to their madonna, and dared not touch her.”

“[At Newport Folk Festival] there were 13,000 people sitting out in the Rhode Island mist. After other performers, Bob went on… Finally, I heard Bob Gibson announce a guest and say a few words about me. We sang, Virgin Mary Had One Son. He played the 12-string, and with 18 strings and two voices we sounded pretty impressive. We made it to the end and there was tumultuous applause. So we sang our “other” song, an upbeat number (thanks to Bob) called We Are Crossing Jordan River. An exorbitant amount of fuss was made over me when we descended from the stage. I realized in the back of my mind and the center of my heart that in the book of my destiny the first page had been turned…”

Joan Baez | And A Voice To Sing With, A Memoir

Albert’s Matchmaking

“I came back to Chicago from Aspen, and I walked into the apartment and a guy says, “Hi, I’m Bobby Camp. Al Grossman sent me. He thought we should sing together.”

Albert had heard him singing with Jimmy Gavin in a club in New York in the Village and said, “I’ll give you a ticket to Chicago.”

He also gave him a key to my apartment. He hadn’t told me about it at all. I called Albert, and said, ‘What the fuck is going on?’ Albert answered, “This guy’s great, he sings great, try him out.”

Camp and I didn’t sing together for several days. We just looked each other over like two stray dogs. Once we started to sing and it was great, I was hooked. He has a great musical ear and a very exciting voice. So I called Albert and said, “Okay, you’re right. I’m wrong. I’ll sing with him.”

Albert said, “Well, OK, good, I knew you would, but listen — I want you guys to get together with this woman and form a trio. Neither one of you are going to like it because she’s taller than both of you.”

He was looking then to form a “Peter, Paul and Mary” type group. But we refused. We didn’t need that!”

A Boy Named Shel

“…those days at the Gate of Horn. It was incredible the people who hung out there, like Studs Terkel and Shel Silverstein. A lot of creative energy around there. Shel started hanging out there in 1958. He was living over at the Playboy mansion then. At that time he was exclusively doing cartoons. The first thing he ever wrote was with Bobby Camp, a song called “The First Battalion.” After that we started to write songs together there. He became one of the most important people in my life.”

Gibson & Camp Combust

“Some performers generate electricity and excitement, charging the very air with their talent. Gibson and Camp went beyond mere electricity to megaton atomic explosions. Gibson on guitar or banjo laying down riffs so easily, so casually, you never realized how complex they were until you heard someone else trying to imitate him.

And Camp’s voice soaring, sliding, hitting notes not yet written and creating harmonies not yet conceived. But beyond the music, there was plain good fun. Camp bouncing one-liners off anyone and anything. Prepared shtick that veered on into wild improvisation–satiric bits and songs on local celebs, the Chicago cops, sacred institutions- even satire on folk music itself. They were only together for one year. Yet anyone who has ever heard Gibson and Camp at the Gate of Horn, anyone who has ever seen them perform together, will never forget the experience.”

Chicago writer G. ‘Gigi’ Gilmartin

Live at the Gate of Horn Liner Notes

By Shel Silverstein

I’ll tell you a little bit about the old Gate of Horn. It was in a basement. I don’t mean a basement club, I mean it was just in a basement. Chicago is full of places like that. It was on North Dearborn Street and there was a door that said “Gate of Horn” and some steps that led downstairs and then when you got down there, it had a sign on the door that said “use other door.”

Gibson would come out of the back with Brown and they would do a few numbers and then he would introduce Camp and the whole thing would start to jell and swing and Brown’s bass would be going like hell and Gibson would be up there cool and cocky, playing that 12-string and singing and Camp would be like a little rooster with his head back screaming and bouncing up and down and it was really something. That bar was really the social center for the hip crowd. Gibson and Camp were the social directors. And they would sit there and whisper and work up wild scenes that couldn’t possibly turn out as great as they sounded.

After a while I think Gibson and Camp even started to look alike. They must have weighed about 45 pounds together and they sat and they whispered and they looked like two crooked English jockeys fixing a race. And they wore those thin grey suits that look like they’ve been made by a shoemaker for an elf, and they each had the cowlick falling onto their forehead just so, and those skinny ties – but there wasn’t anything little about their singing when they did stuff like Betty and Dupree or Daddy Roll ‘Em or – anyway I am not going to tell you how good the stuff is.

I’ll tell you some more about the old Gate of Horn, though. The final night there was really a blast. Gibson, Camp and Brown they were up there singing, shouting and playing and stomping and wailing and yelping and barking and …. if the walls had collapsed right then and there it would have been very poetic. But they didn’t.

— SHEL SILVERSTEIN

Hudson Street, New York City

September, 1961

Aspen 1957 to 1961

Super Skier’s Ski Songs

“I lived in Aspen from about ’57 to ’61. I loved to ski, and I would ski all day and then sing at night in ski lodges to support my family. I was also travelling a lot– to Chicago, New York, and Dallas — to work but I’d always be real happy to get home to Aspen. When it was ski time and the snow was good it was real hard to get me out of town.”

“The first record I did for Elektra was Ski Songs in 1959. I’d had been living in Aspen a couple of years. I started to write some songs with a couple of gals who were writers for the Denver Post. I decided to write a musical about skiing. It was fun to do, and it produced entirely new songs like In This White World and What’ll We Do? and Ski Patrol. I also rewrote a couple of traditional things and put ski lyrics to them. [It was going to be a musical play but it was never produced.] As it turned out, Ski Songs was the biggest selling album I ever cut!”

Glenn Yarbrough’s Limelite

“Bob was a different guy in those days in Aspen. When I got the Limelite club, he damn near destroyed my life before it started. We had done such a good job together the year before when I was leasing the club. When I bought it I went to him and I said, ‘Bob, I’ll give you a piece of this just to work with me, and we’ll work together and we’ll make it go.’ For some reason — I could never understand why, because I was giving him an equal share with me— he went over to the Durham Hotel nearby and made a deal there that I didn’t know about. Suddenly I was stuck with it. I’d put a lot of money into the bar and I had nobody to work with. Luckily, Marilyn Child, who is probably the nicest person in the world to work with, came out to help me.

Turns out Bob screwed somebody’s wife at the Durham Hotel and got fired, so it didn’t make a hell of a lot of difference. But still, even after that, I loved his work, and I loved to work with him. He was a wonderful guy to work with. I approached him in 1958, and I said, “Look, let’s just go into the Purple Onion or the hungry i in San Francisco. We’ll take Marilyn Child, you and I, and we’ll start our own group.” We were all set to go, and then at the last minute again for some reason he changed his mind. I had the gig all set! That’s when they hired the Kingston Trio at the Purple Onion. Instead of us making a success there, the Kingston Trio did. I really don’t know what the problem was. Maybe he was already doing drugs. I don’t know.”

Three Wheel Circus, 3 Kids in 3 Years

My mother Rose, my sisters, Susan and Pati, and I lived in a one-bedroom shanty in Aspen. There was a bigger house on the property that Bob had started to remodel but that project was abandoned. In the winter, it was a world of snow. I remember eating whip cream and cadging martini olives at the Crystal Palace where Rose was a cocktail waitress. My mother’s co-worker, Kathleen, also lived with us for a while. It made the house seem even smaller to have another inhabitant but my mother needed the money to get by. We drank out of jelly glasses, through feast and famine, in an oddly precarious existence, considering how well Bob’s career was going.

I remember seeing Bob’s show at the Red Onion and clapping as loudly as I could at the end of each song. In late 1962, the bank foreclosed on the place in Aspen. We landed in the Bronx where the Prochman family, who had raised Rose from age 2 until she married, once again took her in.

Meridian Green

The Ski and Spur Bar served outlaws and skiers in the spirit of the Wild West. In the 1950s, re-named “The Limelite” it became a lively nightclub with new owner, folk singer Glenn Yarbrough. The Limeliters draw in large crowds, as do other entertainers, from Judy Collins to the Smothers Brothers. Glenn’s rising popularity made running a bar impossible, so he sold it in 1962.

Fired Up in Greenwich Village - 1961 to 1963

A Greenwich Village Talent Agency

“In 1961, Roy Silver, my brother, Jim, and I started an agency called New Concepts in New York City. We had an incredible roster of people, Freddie Neil, David Crosby, Richie Havens, and several others, nearly all of whom went on to do great work. Dylan went on to be managed by Albert Grossman and I then went back to Grossman’s office myself as an artist. But we got some really great artists out there for a brief time.”

Jim Gibson:

“I was living in Seattle in 1961 and Bob was in the Village in New York. He wrote saying, “Hey, I’m putting together a folk music booking and management agency. Why don’t you come join me?” A couple of months later I did. Roy Silver represented Bill Cosby at that point. When he took on Cosby he concentrated on Bill and didn’t do much at the agency himself. I can remember getting Davie Crosby a job over at Gerde’s Folk City. Then Bob and I made a trip to Chicago, and I came down quite ill. [Jim was ill for months.] Unfortunately, during all this the agency just sort of floundered and disappeared.”

Gibson Girls in the Big Apple

Rose and her trio of little Gibson girls spent the long, dark winter of 1962 on Tremont Place in the Bronx, in a studio apartment. Bob lived in the New Concepts office in the Village. A few months later the family moved into a fifth floor walkup on Broom Street.

Bob held court in the living room. Stellar players and their entourages stayed up partying until the wee hours. It was a bit much for family life and the downstairs neighbors so Bob and Shel Silverstein got a basement studio on Hudson Street to continue carousing and composing. Bob still spent lots of time on the road too but was home enough for me to remember lots of trips up and down five flights of stairs carrying his banjo or guitar.

Greenwich Village was vibrant. It was a really big happening, and my Daddy was like, the king or the master of cermonies, so I must have been a princess, and that was okay with me!

Meridian Green

Gospel Pearls on YES I SEE

Bob’s next album was Yes I See on Elektra in 1961. “Jac Holzman couldn’t believe we spent $1,600 to produce it. He was outraged! I thought, “Well, that’s not so very much. You got all the instruments and all those voices and everything.” We had five of the hottest gospel singers in LA, the Gospel Pearls, along with their band, which included a piano player and a bongo player. Tommy Tedesco played on that album. The playing was hot! I love that album! It was one of the first times where a white guy sang with black women. There’s stuff on this album that people weren’t doing until much later.”

Women There Don’t Treat You Mean

“One of the earliest songs I ever wrote, which also became my biggest money-making song, was written at the Gate of Horn. Les Brown [co-owner with Albert Grossman of the Gate of Horn) and I were sitting at the bar one afternoon…talking about this movie I’d seen the night before. It was ABILENE, and it starred Randolph Scott. We started singing “Abilene, Abilene, prettiest town I’ve ever scene, people there don’t treat you mean.”

George Hamilton IV recorded Bob Gibson’s song, “Abilene” in 1963. The song became a huge hit, topping Billboard’s Hot Country Singles and reaching #15 on the pop chart.

Unfortunately, Bob parted ways with Albert Grossman just before “Abilene” became a hit. Maybe if Albert had still been Bob’s manager, Melody Trails, Bob’s publisher wouldn’t have hung him out to dry. When the song hit the charts Lester Brown, Albert Grossman’s partner in the Gate of Horn, suddenly claimed he was a co-writer. Pretty soon there were four songwriters claiming “Abilene” including the pseudonymous Albert Stanton who also claimed to have written “The Lion Sleeps Tonight.”

Read more about GATE OF HORNING IN…on the Abilene SONG page.

Someone’s Kidding, My Lord, Kumbaya

“I started a “hootenanny” at The Bitter End. It was a coffee shop having poetry readings and bongo drum players when I said, “Hey, let’s put some folk music in here,” to the owner, Fred Weintraub. I asked Ed McCurdy to be the host. Ed was well respected, but not in any particular genre. That way the host didn’t put any particular stamp on the occasion, like it was going to be this kind or that kind of show.

Fred got the guys from Ashley Famous Artists, an agency producing television, to come down. I put together a one-hour hootenanny for them. It was a Tuesday night hootenanny, but a very special one. They saw it and said, “This would be a great television show. We’ll do it with a live audience, just this way.” The program debuted in April, 1963.

The producers blew the most important concept of all. They didn’t get the idea that they should book an artist and say, “Do whatever you want in your slot.” Rather they’d ask, “Why don’t you do that song?” The producer — the person who was creating the show — was always working with a known palette. No spontaneity.

For instance, [when] Josh White was there and they were deciding what songs Josh was going to do. He did a little bit of Strange Fruit. If you’ve ever heard Josh White, you know he would absolutely put an audience away with that song. His voice wavered a little bit, and it was a very difficult song for him to sing … Nevertheless, the song was mesmerizing, but all they could hear was that his voice wavered. It wasn’t a pure clean tone. They said, “No, let’s not do that one, let’s do something else.” Those guys used to make me nuts!

I evolved this “Let’s all get together and do a ‘come all ye’ type of song” at the end. It’s great when artists are willing to try and make music together. They were doing Kumbaya [for the last song] in a terrible key and doing too fast. They would shoot somebody doing a verse and then they’d back off and show a whole shot of the assembled cast singing it. They’d roll the credits over it, then they’d zoom back in again. I got to my verse and I didn’t think they were zoomed in, so I sang, “Someone’s kidding, Lord, Kumbaya…” Well, that’s what made the final cut. The producer saw it and I didn’t work there again.”

Greenwich Village 1964 to 1966

Where I’m Bound

“There was a very big gap then before I recorded my next album, Where I’m Bound, in 1964. By then I was getting nuts… really self-destructive.

I was writing and wasn’t interested in doing traditional too much, or the traditional I was doing hardly related to the traditional form anymore.

On Where I’m Bound, there’s a version of Fare Thee Well or Nora’s Dove, and the credits on it are me and the Lomaxes. Because it was such a distinctive arrangement, the Lomaxes said, “For this arrangement you can put your name on it — for the arrangement only.” That was a hard estate to crack. In this case, however, they were very cooperative.”

The Real Dope

“During the late ’50s, I would get stuff to use on long driving trips for gigs. There also would be the late hours, working around the clock… a certain amount of social drinking that would tend to get you fuzzy. Then I’d drop something to get over feeling fuzzy and that would make me edgy. Then I would smoke some grass to take the edge off. That was terrible pharmacology, trying to get feeling okay. But that was the reason I felt different from most people using drugs. I told myself I was just trying to get feeling okay. Then there were store drugs that began to arrive on the scene. You didn’t even need to get street drugs. I got bogged down in it all. My drug use escalated again when I discovered heroin. I took to it like a duck to water.”

Farewell and Goodbye, Gone Again

“The music of Bob Gibson is unlike the music of any other folk artist. For throughout the ‘folksong revival,’ there have been the originators and the imitators. Bob Gibson could be nothing else but an originator, a creator, a prime mover…Not only is Bob a magnificent instrumentalist and showman, extraordinary composer and arranger, but he has an uncanny eye for discovering new talent. He was the first to introduce such highly respected artists as Joan Baez, Mike Settle, Bob Camp and Judy Collins. Except for Pete Seeger, no single figure in recent years has influenced the folk field in as many diverse ways as Bob Gibson…Every album that Bob has made has provided material and musical ideas for other folksingers. Indeed, it is difficult to find a folk group album which does not contain at least one Gibson creation…”

Liner Notes from Where I’m Bound

Bog Hollow Road 1966 to 1968

Intoxicating

We moved from Broome up to Houston Street, to a larger three-bedroom in a building with an elevator. There were lots of ups and downs and a financial roller coaster ride. My mother was a paragon of frugality. Any money comes her way, she puts aside for a rainy day of which there were many.

My father’s approach was, “Quick! Spend it ’til it’s gone!” When he had money in his pocket he wanted to buy a round for the house, eat lobster, drink champagne, and buy another round until it was gone! He spent it as fast as he made it– faster. He was frantically generous trying to buy his way out of broken promises and to keep the party going. His addictions to everything grew enormous, bigger than life, faster than a speeding train, higher than a kite. When he ran out of party he’d flatten out like popped balloon, hole up in the bedroom and self-prescribe chemically-induced R & R until he was ready to soar again. When he had his chemistry working he was so wickedly beguiling, so intoxicatingly charismatic that people became addicted to him.

Daddy disappeared for a while when I was 9. I didn’t know what was up until I found a letter in my mother’s purse from a Toronto jail. The letter was about what she should do to raise the money for his bail so that he’d be home in time for Christmas. That was when I learned my father’s “medicine” was illegal. It was also, I think, when the fast slide really began. A year or so later, we moved from Greenwich Village to Wassaic, in upstate New York.

Meridian Green

Bob tells this story in his song Box of Candy (and a Piece Of Fruit).

The Geographic Cure

“I left the business in ’66. It seemed to me working in clubs, being on the road, being in show business and around musicians [caused]me to use drugs. I thought if I got away from that, everything would be fine. I decided to try the “geographic cure.”

I spent almost three years up in the country with the wife and the kids, trying to be the father and husband I had never been; trying to completely quit drugs. I had always liked working with wood, so I set up a wood shop there. I collected antique wood working tools.

It didn’t work. I’d just go into the city on the weekends to get high or I’d write my own prescriptions for speed and stuff.

The marriage broke up during that time. It was very painful. I was trying very hard. Of course, that was the solution Rose and I had to all our problems – to try harder. And we truly did. Sometimes I would be madly in love with some other woman, but then I would think, Rose is the woman I chose. We’ve come along this far. We’ve got kids and all. We’ve just got to try harder, which we both would.

At this point, out in the country, I must have been really odious to be around, because now I was going to be the gung ho father and husband I’d never been during all those dope years. So I was around. But who was around? I was out to lunch all the time.”

Wassaic was hell

“In late ’66, we moved so Bob could ‘get well’ living in country. What a doomed idea! As I metamorphosed from a confused child into an angry adolescent, I was incensed about taking instruction about anything from a man who had made, and was still making, such a mess of own life. Bob was at the very bottom and still digging himself in deeper. By the time he moved his mistress into the living room, I just wanted him gone.

He did try for a while, in his own peculiar way, to make a go of this family life in the country show. He got a couple of cats. We had 28 kittens within a year. He got a goat named Spinky who ate herself death a week later. He got a cute pair of German Shepard puppies, both male, who soon fought all the time. He became obsessed with the idea a pet raccoon.

First, he needed to capture a pair of raccoons to breed so he spent long, sleepless nights driving around with a flashlight and a trap. He stayed awake, around the clock for weeks, trying to catch raccoons. We’d wake up in the morning to the find the family patriarch passed out at the table, face in his cereal bowl. We stopped using the front door so the pair of feral raccoons he eventually caught could spend months in the glassed-in front porch, glaring at each other in a totally non-reproductive way.

Bob disappeared in the spring of 1968. When he left, we let the raccoons go and we never saw them again.”

Meridian Green

A Hole In Daddy's Arm

Woodstock to Hollywood

In 1970, Bob was playing Sam Hood’s club, the Elephant, in Woodstock and hanging at Tim Hardin’s. He finally had a pet racoon, a rescued orphan he’d named Rocky. Rocky became friends with our family dog, Oopie, while Bob was traveling. Playing with dogs was Rocky’s undoing. He was playing with Tim Hardin’s dog when he died.

Rose was emerging from a scary spell of depression and having a personal Renaissance scored by B.B. King’s “The Thrill Is Gone.” Susan and I were careening into our teens, pedal to the metal, racing towards adulthood as fast as we could go, with Pati trying hard to keep up.

The family disintegrated further that summer. Susan went to went to live with Bob, first in Chicago and then California. Rose and Pati moved to Florida. Not quite fifteen, I struck out on my own. A year later, both Susan and Pati were living with Bob in California when Rose persuaded me to come to California with her.

Rose had painted “L.A. or Bust!” on the hood of the same 1960 Dodge that had gotten her to Florida, loaded up Oopie, and came to fetch me in Greenwich Village. Oopie, still searching for Rocky, tore a hole in the box spring of every motel bed along the way. Rose and I drove through the Mojave desert on a boiling July day to arrive, weary and wilted, at the Troubadour, in Santa Monica, where Bob was playing and the girls were waiting.

Susan and Pati had been living with Bob in a rehab program. When Rose found a one-bedroom apartment in Hollywood on Beechwood Drive, the four of us were soon packed in together. I worked at the House of Pies on Hollywood Boulevard, saving money to go back to NYC.

Meridian Green

Flying Burrito Brothers

Bob’s Capitol album featured members of the Byrds and Flying Burrito Brothers.

Sam Stone Estopped

“By 1971, I was out in LA making an album for Capitol called Bob Gibson. There was a great reunion… folks I hadn’t seen in ages, David Crosby, Roger McGuinn, Spanky McFarlane, that whole gang. They were all beginning when I was already established in the early ’60s. They had all gone on to do amazing things. The album was sort of a hodge-podge. It was my first exposure to multi-track recording.

John Prine’s Sam Stone was on my album [which] came out two weeks before his. We were getting a lot of airplay when [Prine’s record label] enjoined the album in court. Jerry Wexler said, “Oh, my God, we can’t have this going out before John’s original version.” John was the only singer on his version. I had all these people singing on it and it was a great version. The FM stations were playing it like crazy, but… it didn’t happen. That was it for the Capitol album.”

Next Stop Mendocino

“I moved up to Mendocino in late 1971 and spent a couple of years there up in the redwoods, along the Pacific Ocean. It was very colorful. There weren’t many jobs for me [so I’d go out and work] in clubs Chicago and Los Angeles. I was just hanging in, doing the same set of songs and I wasn’t writing or learning. Shel Silverstein was very helpful in jarring me out of this. Shel would come up there and we’d write songs.”

Bob and his daughter Pati in 1971.

Tarot and the Banjo

Songwriter, astrologer, and lifelong family friend, Antonia Lamb said, “When Bob came to Mendocino we had this incredible musical community here and everyone embraced him with open arms. There was music everywhere. It was just an incredibly fertile time and Bob started writing again. There was an atmosphere in Mendocino at the time that reminded me of the early Greenwich Village days… it was a vital creative community and it inspired everyone who was here.

“[When] I was in Hollywood, Rose (Bob’s ex-wife), Pati, Meridian and Susan (his daughters) moved right down the road. I got friendly with her and the kids. Then, when Pati was 13, she came up and lived with my family for a while [until] Bob had his own place up the road. Later on, Meridian moved here, too. [And eventually Rose moved too.] It created a web of life-long love between us all.”

Bob, Antonia Lamb and Biff Rose – 1971

Living Legend

“Ain’t it great to be a living legend?”

When Bob Gibson sings the words to this gently ironic song, written for him by Shel Silverstein, he does so without bitterness. Bob’s love of the music – and his ability to make it fun – heralded, then profoundly influenced, and eventually outlasted the heyday of the folk revival. He was one of the earliest pioneers of the great folk boom but the great folk boom was bust. Bands like the Byrds and Buffalo Springfield had acknowledged Bob’s inspiration but even the folk-rock era was biting the disco dust. In 1970, a classic music business snafu torpedoed Bob’s last major label release.

So, innovator that he’d always been, Bob started one of the first artist-owned, record companies. “Funky In The Country” was released in 1974 on Bob’s own Legend Enterprises label. At the time, it was a novel approach. Recorded live at Amazingrace Coffeehouse near Chicago, this album showcases Bob’s trademark bass runs on his ringing 12-string guitar and his warm rapport with the audience. It’s a homegrown masterpiece of simplicity.

Billboard said “One of the finest singers in American folk history returns to the recording scene with a fine live set. Gibson’s vocals sound as strong as ever.”

“Funky In The Country” and the whole concept of the Legend Enterprises label got off to impressive start. It seemed poised to take, if not the entire country, than at least the mid-west by storm. Bob had a summer full of concerts and record release events scheduled. The album was garnering rave reviews. Sadly, Bob’s first stop on the road to promote his new album was a few months in rehab. By the time he was once again ready to travel, the momentum had moved on.

Traveling troubadours routinely bring their recordings directly to the audience now but once upon a time record companies did not let artists sell albums at shows. Bob always had uncanny sense of ‘the next big thing’. He was a legendary discoverer of new talent and spotter of trends. He was one of the first artists to perceive the coming sea change in the music industry and to explore the uncharted territory of the artist-owned record label.

Funky in the Country

“Funky in the Country came about backwards. I was playing at Amazingrace, a coffeehouse in Evanston, Illinois, with John Guth, a terrific guitarist. The ambience was very special there.. We decided to try and make a recording of the performance.

We got lucky. When you realize that what you’re saying is being immortalized on tape, you tend to blow it. We didn’t think we were going to have a tape. The mikes were so poor, we just forgot about the whole deal. But someone borrowed some great mikes unbeknownst to me, and while I was up there singing, over being self-conscious and free of worries about making an impression on the machine or the audience, the people at the controls were getting a great tape.

I knew I’d never record with another major label. It would just be the same old situation and that wouldn’t suffice. You read about $75,000 to $100,000 to do it right and everything is deductible from the artist until the company starts showing a profit. Then the album has a short shelf life. You can’t get them to reprint small batches to keep the stores stocked. The pressing just disappears even though you need to have your name and albums out there.

I took the recording we’d made to try to drum up some support for producing it in Nashville. [When I played the tape for Ray Tate and John McGuire, they decided to back the record themselves.] That was the beginning of Legend Enterprises.”

The Legend of Legend Enterprises

I was working as a waitress, intending to return to Mendocino with means to buy a cabin and a car, when I found myself entranced by an even bigger dream, Bob’s dream of Legend Enterprises.

It was brilliant and way before its time. Today just about anybody who’s ever made a record, and for sure anyone who’s ever had to deal with a record label, big or small, has at least thought about having their own label. But in 1974 it was a relatively novel idea born, I think, out of his frustration with how the Capitol deal had gone down.

Bob’s idea was to make Legend Enterprises a little homemade label that could profitably sell 5,000 to 10,000 records. He knew he could sell that many albums directly to his audience at concerts and clubs in the mid-West. It made perfect sense to me and I was thrilled to be involved in the launching of Legend Enterprises.

The Living Legend (Shel Silverstein)

“When Shel wrote Living Legend and brought it to me, I said I couldn’t sing it, it was too close to my life. He insisted. “Go on, sing it,” he said. I listened to it a few times, tried it once. It felt good.”

Hey Mister-can you use an old folksinger

Would your patrons like some old time soul

Can they dig the “Foggy Mountain Breakdown”

Sorry I don’t play no rock ‘n roll

But I can make’em cry to “Molly Darling”

Sing along to “Row Your Boat Ashore”

I’ll play until the dawn and

When the crowd is gone

Mister, I’ll be glad to sweep your floor

You should have been in New York back in ’60

Hey, wasn’t I a star there for awhile

But New York messed up my head

Got strung out on reds

Bobby Dylan went and copped my style

Oh, but I can make’em cry to “Molly Darling”

Sing along to “Row Your Boat Ashore”

Street life sure is fun

When you’re twenty-one

But, Mister, I ain’t twenty-one no more

So, I take the love of them that still remember

Take the help from them who care to give

Swap my songs for sandwiches and shelter

Even living legends gotta live

Oh, but I can make’em cry to “Molly Darling”

Sing along to “Row Your Boat Ashore”

Michael, row your boat ashore

Hallelujah

Michael, row your boat ashore

Hallelujah

Michael, row your boat ashore

Hallelujah

Concert Review

“Bob Gibson, who opened Tuesday night at the Boarding House, is today’s living legend. Although his career as a name folksinger spans more than two decades, he has never before played a regular gig in San Francisco. He did one audition set many years ago at the hungry i, at which point he says, “Enrico Banducci and I agreed to disagree” — some say blows were exchanged. He played only once in the Bay Area, at the Lion’s Share several years ago. Now, he says, “after a long dry spell,” he is busily churning out the tunes again and has hit the road to lay his handiwork in front of the folks. Gibson’s first set on Tuesday was a delight. He is a buoyant, personable, humorous presence on stage, and his songs are likewise.”

John L Wasserman, San Francisco Chronicle, April 1, 1977

Reborn

One Day At A Time

In 1978, Bob found a new way of life in AA.

“Somebody said to me, “It ain’t how good you are, it’s how long you’ve been around.” That may sound like a cute, facetious line, but I really felt that way. At long last, I’d lasted long enough to integrate a whole lot of that stuff, and it became pure joy to do it. I didn’t have any more goals. I wasn’t doing it for anything. I was doing it because I liked doing it. It’s a great joy to be happy in your work.

I was writing again and really considering my show — not just doing what seemed right or what felt right — I really was giving it some thought. I wanted to try to reach out and stretch out and do some new stuff. I was ready take a chance. I’m very slow to change– scared to death of change– but change was all I felt I’d accomplished. Through no good grace of my own, I was still around and whatever I had to work with wasn’t gone, either, so that was a major accomplishment.”

Robert Josiah Music

Bob started a publishing company, Robert Josiah Music, named after his first grandchild, in 1978. After almost 40 years of effort, his song catalog is nearly all administered by Wixen Music. Randall Wixen wrote Plain & Simple Guide to Music Publishing. Had this book been available in 1978, Bob would have known how to reclaim his songs in 1988, when he first had the right to take them back from TRO. Instead TRO has been squatting on the Bob’s ‘intellectual property’ for 28 years.

Sing For The Song – Take 2

“Camp and I cut, Homemade Music, in 1978. At the time I said, “If it does as well as the last one, we may make it a habit to record a new one every 18 years.” It not only reunited me with Camp, but with an old friend of mine, Dick Rosmini. Dick is an engineer and a musician. He can do just about everything. He played on all the tracks — bass, mandolin, synthesizer and everything – and he recorded the album in his home. Even the picture on the cover was taken by Dick on his front porch.”

An Album Review

Homemade Music is a thoughtful and perceptive album that in a sense, biographical — for Gibson, Camp and writer Shel Silverstein, their long-time friend and songwriting collaborator. Gibson no longer is the cocky kid singing All My Trials without ever having had any. Homemade Music provides insight into just how hard and long the road to personal maturity was for Gibson.

Gibson and Camp were together for only one year. Camp, a child star in the “Our Gang” comedies, left Gibson & Camp for Second City and other acting work. But the sound they always have had is still there. Homemade Music also features the producing and musical virtuosity of Dick Rosmini who backed up Gibson (& Camp) on guitar at the 1960 Newport Folk Festival.

The sound Gibson and Camp always have had is still there. Gibson explains the essence, “Either of us is likely to have the high or low harmony at any given moment. Then there are times when we cross over and even kind of pound away with no melody. We actually get the melody out in two or three passes of a chorus. Then we both sing harmony. The melody is still evident because people are still hearing it in a shadowy kind of way in their mind. We almost are getting three-part harmony, with the third part in your head.”

Nick Schmitz

Daily Herald, Sept. 1978

Kerrville Songwriting School

In 1978, Bob started going down to Kerrville, Texas to take part in Rod Kennedy’s Kerrville Folk Festival, which now has become the longest running folk festival in existence. To this day, for two weeks around Memorial Day, folk artists from all over come together to make music. Not only did Bob love to play there, but it was at Kerrville that he began teaching songwriting.

Rod Kennedy, Kerrville Folk Festival said, “Bob had been one of my heroes forever and I don’t really remember how I got in touch with him, but I asked him to come and play, and he talked to me about starting a songwriting school. He started the school in 1979 and he ran it until 1991.”

The Songwriting Manual Bob developed is still a useful resource for songwriters today.

Playing and Writing with Tom Paxton

Bob kicked off this era with a series of reunions. Tom Paxton remembers, “After Bob got sober in 1978 I met him again in San Francisco, and we became real good friends. Right away we started writing together.”

A Concert Review

“Bob Gibson and Tom Paxton reaffirmed the participatory quality of folk music in a delightful program at the Cellar Door last night. Both songwriters must be counted among the survivors from the early ’60s folk revival. Paxton in particular has maintained his songwriting skills, alternating between sharp wit and poignancy to bring subjects home.

Bob Gibson has not been very visible over the past decade, and his charm and considerable talent make one wonder why. His 12-string guitar work was a major influence on musicians in the early ’60s, and his return to performance is a much more important event than the reunion of Peter, Paul and Mary. That trio probably conjures up more images of the folk days than Paxton and Gibson combined, but, as so often happens, the real vitality and talent emanate from songwriters and performers like these, who quietly ply their trade.”

Richard Harrington

Washington Post, July 1978

Perfect High

Right Size For Folk

The Bob Gibson In Concert video recording begins an interview. Bob talks about preferring to play music in saloons or small rooms, that giant concert halls and stadiums were never a good fit for him. For all the furor in Bob’s early career about ‘tradition’ and the liberties he was taking with the songs, I’ve come to believe that his fidelity to folk music as an intimate art form is one of the important ways he spread the tradition of folk music. Bob loved to play small clubs for longer engagements as was typical in the early days. Those cozy rooms, packed with people who came to know one another as well as the songs, were tribal. There are studies now that show people thrive in village-size groups of a hundred or folks where they become familiar enough with one another to develop functional relationships.

Over the next decade, Bob wrote plays and opened a night club of his own. In part, it was an effort to recreate that essential mix of intimacy and continuity that got lost as troubadours found themselves playing endless one-nighters in an ever more anonymous world.

Meridian Green

Drollest Album Yet

By 1980, with a couple of years of hard won sobriety under his belt, Bob Gibson was having enough fun to record “The Perfect High”. His self-deprecating humor, gentled by compassion for his own flaws, gave rise to his drollest album ever.

Shel Silverstein wrote a lot of the songs on this record. “Yes, Mr. Rogers”, “Cuckoo Again” and “Middle-Aged Groupies” are as much cartoons as songs, animated by Gibson’s dexterous delivery. “The Perfect High” is a full theatrical production, with a multi-character cast, in which Bob plays all the roles.

Gibson and Silverstein also co-wrote two of the album’s most profoundly humorous songs. Based on true stories from Gibson’s life, “Just A Thing I Do (Kathy O’Grady’s Song)” and “Mendocino Desperados” are more than brilliantly crafted songs. Gibson’s willingness to tell on himself generously gives us all a chance to get over our embarrassments, whatever they may be.

Gibson is joined by co-writer Tom Paxton on “Box of Candy (and a Piece of Fruit)” in a rowdy duet telling the tale of Gibson’s Yuletide incarceration in a Canadian jail. Anne Hills’ adds hauntingly beautiful harmony to “Leaving For The Last Time” and “Army of Children”.

KXRT-FM Broadcast from Navy Pier

A great recording of a wonderful duet show by Bob Gibson and Tom Paxton resurfaced on 2016. It was recorded, produced, and hosted by Rich Warren during Chicagofest at Navy Pier Auditorium, AUGUST 7, 1980.

Best of Friends

Green River – A Love Letter to Chicago

In 1982, Bob joined with Thom Bishop, Ginni Clemmons, David Hernandez and Michael Smith to produce a show entitled Chicago: Living Along the Banks of the Green River. It featured new songs from each of the artists about the Windy City. It opened up new avenues for Bob who went on to develop another musical play.

Best of Friends

In 1984, two generations of master folksinger-songwriters – Tom Paxton and Bob Gibson – teamed up with relative newcomer Anne Hills, who would soon gain recognition as their peer, to perform for 18 months as Best of Friends.

Although both men already had lengthy and successful solo careers in progress Paxton said, “By the early ’80s, Bob and I wanted to work together more often,” “and when our manager suggested adding a woman’s voice, we agreed and never thought of anyone but Anne.”

“Bob produced ten albums of mine. He produced the two albums I did for Mountain Railroad, and he produced the album I did for the company he and Anne Hills had, Hogeye. He did a couple of the albums I did for Flying Fish and several children’s things, and we worked and performed together. Then we formed a trio with him and Anne Hills and me so we were tight buddies, Best of Friends.”

Appleseed Records 2004

The group never released a recording during their time together but in 2004 Appleseed Records released an album recorded live at Hobson’s Choice in 1985. It featured Bob, Anne, Tom and Michael Smith on bass.

Uptown Saturday Night

Uptown Saturday Night was a studio album co-produced by Anne Hills, Rich Warren and Gary Elghammer. It includes some of Bob’s best crafted, most enduring songs including Let The Band Play Dixie, And Lovin’ You, and Lookin’ For The You in Someone New. Pilgrim is considered by some as the unofficial anthem of AA.

THE COURTSHIP OF CARL SANDBURG

My Theatrical Experience

I’ve had a firm belief as a songwriter and a creative person interested in a kind of story-song, music and songs that have content, that it was only a small transfer to really move out of saloons into small theaters. It’s a natural development for a songwriter to become a playwright. A play is a sort of an expanded song. Organically, they’re alike. Both have a beginning, a middle and an end. Both have characters and a point of view. Both state a problem, or ask a question, or capture a feeling. But the song is self-contained, and especially when you sing your own, you don’t have to depend on anyone else. Theater makes a lot of sense. There are fewer and fewer saloons and a lot of the songs I write are just mini-theatrical experiences.

I didn’t set out, though, to write a theater piece. I’ve always been fascinated with Carl Sandburg. In 1927 he published The American Songbag, the first compilation of American folk music. When I began with folk music, the Songbag was one of my main sources.

Then I actually met Sandburg. I was part of a project to read and record Sandburg’s poetry and provide a banjo accompaniment. It was in the ’50s and here I was, a young folksinger most people hadn’t heard of. And there he was, poet Carl Sandburg, an imposing, white-shocked chunk of Americana. I cautiously said, “I was wondering if you have a few moments to spare?” His response was, “I’m at an age when I don’t have any moments to spare.” I immediately decided I liked the guy!

I always kept in mind doing something in tribute to Carl Sandburg.

It was a two-act play that was kind of like a scrapbook, based on Carl Sandburg’s life, his papers and letters he wrote. Sandburg was an intensely private man but in his letters, he couldn’t hide out that much. He wrote great, poetic letters. Letter writing was such a wonderful thing at the time. Now nobody ends up with a pile of love letters tied up with a ribbon. All you end up with is a bunch of phone bills.

Sandburg was an early media product. After he became famous, he was careful that what he did worked for the Sandburg image. Big Fourth of July spreads for the Saturday Evening Post. That sort of thing. He knew he was a star.

Well, at this point in his life (his early 20s, the period covered by the play), he was a real hustler. He wasn’t sure exactly what he wanted to do, but he wanted passionately to succeed. He was star-bound and he was wildly enthusiastic about Lillian Steichen, who he eventually married.

Hobson’s Choice & Chili Bar

Bob became a partner in a place on Clark Street in Chicago called Hobson’s Choice.

“I was trying to run a place with certain kinds of principles and goals– a wonderful place for people to perform with anl intimate room and a real connection between performers and audience. Instead of doing one-nighters, I had them come in for longer periods of time, like two to four weeks.”

Josh White Jr. on Hobson’s Choice:

“Hobson’s Choice was a bar that Bob took over that had a performance area and then a bar outside. It was special because it was so respectful. As I remember it, the bar was situated so that if there were people who didn’t particularly want to come in or pay the cover to see the music, we were not disturbed by them. That, as I remember it, was very important. There is nothing worse than having a listening room that is not a listening room. That’s the way the Gate of Horn was, too.”

Gibson & Camp Revisited – 1986

It’s amazing how many people asked me, “Where can we get that album you guys made?” I’d say, “You can’t, it’s no longer in the catalog.” So as a 25th year reunion concert, Camp and I made the album again. We added three songs. Other than that it is the exact same album. There’s more energy to the second album.

’60S Folk Heroes Still In Tune

A great song remains a great song, they seemed to be saying… their musical intensity and conviction seem undimmed. The warmth of their voices and the urgency of their message transcend musical fashions. Beyond the verbal dexterity, there’s the simple pleasure of hearing them play their instruments, from Gibson’s banjo and guitar to Camp’s plaintive harmonica.

As always, the duo is a shade under-rehearsed, leaving to chance what others plan in great detail. For the listener, the joy is in the spontaneity of it all — Gibson and Camp simply do whatever strikes their fancy at the moment, and it’s anybody’s guess what they’ll sing or say next. In an age of carefully calculated music videos and slick-surface performers, what could be more appealing?

Entertainment writer, Howard Reich

Flying Whales and other Tales

Gibson & Camp – Father’s of the Groom

The story of Gibson & Camp is not complete without the story of the reunion, as the fathers of the groom, at Stephen’s wedding in 1988. But first, some background. Bob and Rose Gibson got married in 1952, and by 1959, Rose was the mother of three children, and Bob was the father of four. Stephen was born to Jovita, who later married Bob Camp and changed her name to Rasjadah. Stephen learned the truth of his paternity when he was fourteen.

A couple of years later Bob, his girlfriend Debbie, my sister Susan, and I were living on Wilton in Chicago. Stephen came to live with us briefly because he wanted out of Skymont, Virginia. Later on, when he was living with the Camp family again, in Los Angeles, he fell in love with the girl next door. Seannie McRae was 16 and her parents thought she was too young for this relationship but their love lasted and Stephen and Seannie’s wedding in 1988 was the truest ever Gibson & Camp reunion.

We were all there, both clans – Stephen’s mother Rasjadah, and five siblings on the maternal side, my mother, Rose, and Stephen’s three siblings on the paternal side plus two grandchildren, and Bob’s new wife Margie, with a wee bump that became Sarah. It was a colorful event with quite a cast of characters assembled in the garden of the McRae’s. The families of the former Skymonters, including the famous Arquettes attended. The bridesmaids were resplendent in extraordinary shades of orange and yellow. Dr. McRae, in full Scottish regalia, including kilt and bagpipe, escorted Seannie down the aisle.

As gloriously beautiful as the bride was, as poignant as the love story that led to this wedding still is, for me the significance of the day was this — Gibson and Camp as fathers of the groom, acknowledging that together they had a son, Stephen. It was the only time we ever all gathered together, the clans of Gibson and Camp. That’s who Stephen Gibson is, the embodiment of Gibson & Camp.

Meridian Green

Uncle Bob’s Place

“[Too much] kids’ programming was created by toy and cereal companies. It used to be that they just advertised, but then they started selling the kids stuff — no attempt at any real content. I set a goal of holding children’s attention with stories and songs about feelings rather than odes to consumer goods. With kids, once they love a song, they’ll sing it over and over and really learn it. It becomes their tune.

The first thing you need to understand in writing music for kids is that there’s no such thing as a “just a children’s song.” Kids’ music requires at least as much thought as adult lyrics. Two things kids love are ghost stories that let them be scared without actually being in danger, and the chance to do something outrageous without having to worry about getting into trouble. Also kids will go along with all kinds of things if they’re having fun with it because they haven’t yet learned it’s important to be cool, so they’ll make funny sounds and faces with you.

I did about 15 shows as Uncle Bob at Holstein’s in Chicago, honing my skills and videotaping the audience from every side to see what they were reacting to. It blossomed into “Uncle Bob’s Place” when OshKosh B’Gosh sponsored my tours. I performed free shows in malls all over the country, and I wore bright blue or red bib overalls, just like the little kids.

Kids (three to nine years old) have the same concerns that you and I have got. They have the same emotions. They just have a limited vocabulary, and a limited life experience. They’re not interested in abstractions at all! First of all they want to be entertained. Their first priority is they want to know, “Are we having any fun?” It’s real simple! But they also are wide open to being stimulated, or educated, if you will. So fun with a message was what Uncle Bob’s place was all about.”

Flying Whales and Peacock’s Tales

“One of my proudest achievements was the Uncle Bob television series we put together, Flying Whales and Peacock’s Tales. It was carried in 1989 on WMAQ, the NBC affiliate in Chicago, and was even nominated for an Emmy. I had a group of five kids join me in the studio, and we’d sing songs together, they’d draw pictures and we’d talk. It was a lot of fun. The master tapes were edited into a series of ten video cassettes that were sold to schools.”

A Child’s HAPPY BIRTHDAY Album

“For several years I was totally focused on the youth market in music. During the Uncle Bob years, I produced four albums of original songs for children for Tom Paxton on Tom’s label, PAX Records. Then finally in 1989, I released my own children’s album on my label, BG Records. It was called A Child’s HAPPY BIRTHDAY Album, and it contained twelve new and original songs about birthdays. Ten of the songs I co-wrote with Dave North, and two of them were done with Shel Silverstein.”

Stops Along The Way

Sarah Louise Gibson – 1989

Bob’s youngest child was born when he was 57. His wife Margie stayed in Chicago when Bob moved back to Mendocino, California in 1991. Sarah returned to Chicago after college and is a teacher.

Stops Along The Way

On Bob Gibson’s 60th birthday, (November 16, 1991) he invited about 80 friends to a recording session party at Bill Goldsmith’s Paramount studio. Speakers were set up around the room directed so that the audience could hear themselves as they sang along with Bob. As Lynn Van Matre of the Chicago Tribune said, “The mood was warmly informal, with guests singing along from time to time. The songs were a mix of old and new, including traditionals such as Michael Row the Boat Ashore and No More Cane on the Brazos, as well as more contemporary, socially conscious fare.” The songs represent “stops along the way” in the career that, at that point, had lasted 38 years.

Bob headed out to promote the new album but was having experiencing physical symptoms that were the first signs of PSP, Progressive Supra-nuclear Palsy. Bob decided to move back to his beloved Mendocino.

Makin’ A Mess

Bob’s problems continued to intensify after Stops Along the Way. By 1993, he could no longer play and still didn’t know what was going on. For some time, Bob and Shel Silverstein had talked about doing an album with Bob singing Shel’s songs. Bob was uncertain that he could pull it off. Shel said he’d get Nashville studio musicians and friends to help out on instruments and vocals.

The album was nearly complete when Bob received his diagnosis. On one hand, it was a weight off his shoulders to know at last what he was facing. On the other hand, the news was grim, and everyone now knew this would be Bob Gibson’s last recording effort. The one song remaining to be cut was I Hear America Singing. Shel put out the word, and in no time, he had assembled a magnificent tribute to Bob.

Bob Gibson Folk Reunion

(top row) Cathryn Craig, Tom Paxton, Peter Yarrow, John Hartford, Emmylou Harris, John Brown, Producer, Kyle Lehning. (2nd row) Dennis Locorriere, Oscar Brand, Bob Gibson, Ed McCurdy, Glenn Yarbrough (bottom) Barbara Bailey Hutchinson, Shel Silverstein, Spanky McFarlane, Josh White Jr.

Loving Homage to Gibson

On July 25, 1994, many of the greatest names in folk music, past and present, gathered in Nashville to record I Hear America Singing, the final song on Makin’ a Mess: Bob Gibson sings Shel Silverstein. The album is, in one sense, a tribute by one of the most influential and enduring voices in folk music to one of the most unique songwriters ever to embrace the format. The climactic Nashville session, though, was a loving homage solely to Gibson, himself.

While recording the album, Gibson was diagnosed with a form of Parkinson’s Disease. I Hear America Singing, an inspirational anthem in its own right, took on deeper significance as a celebration of an artist who has not only touched all those who made it their duty to come to Nashville to sing along, but so many like Silverstein, who credit Gibson as a mentor. (see above)

Asylum Records Liner Notes

Bob & Shel, BFF

“And what I owe him — what he did for us — was he set the time for us and I know that to be there was to be the best place in the world. I’ve never had anything better. I think it’s important, you know, for us to know that — that we were at the best place at the best time.

I had a band once with a clarinet player — his name was Joe Moriani. Later on when Louis Armstrong passed away, they interviewed Joe and they said that we know how much you loved Louis Armstrong. Joe Moriani said, “No, I don’t love Louis Armstrong.” He said, “I am Louis Armstrong!” And this is true. This is true.

I don’t just love Bob Gibson. I am Bob Gibson. Because what he was comes into me and it comes out in the other stuff that I do, and maybe what I am goes out to some other people, not just to affect them or to entertain them — but that’s enough if it was that — but we do become them and pass them on. So I thank you for coming into me and letting me pass that on.”

Shel Silverstein

It’s impossible to listen to Shel’s songs, the ones he wrote about Bob, or to hear the songs they wrote together without being blown away by the warmth and depth of their friendship.

The Benefit

When Bob was no longer able to work his friends came to his aid. Peter Yarrow, of Peter, Paul & Mary, along with Jom Hirsch of Old Town School of Folk Music and WFMT radio (Midnight Special) organized a sold out benefit concert. A standing room only crowd paid $25 to $125 a ticket to hear such luminaries as Peter, Paul and Mary, Roger McGuinn, Hamilton Camp, Josh White Jr., and Spanky McFarlane pay tribute.

McGuinn reminisced about when he first heard Gibson play. “When I saw Bob that day, it changed my life,” he said. And that is reminiscent of what Bob said about meeting Pete Seeger…

Although the headliners were Peter, Paul and Mary, the reunion of Gibson and old partner Camp was the night’s highlight. They harmonized as if time had stood still on Well, Well, Well, and Abilene. Gibson fittingly stole the show with a rousing I Hear America Singing, which underscored that this folk legend isn’t giving up without a fight.

Dan Kening, Chicago Tribune

Bootleg Gibson – A Benefit CD

Jeff Chouinard, the sound man at the Quiet Knight and Mother Blues, and Guy Gilbert, who played bass with Bob over the years brought BOOTLEG GIBSON cassettes to sell at the concert to help raise funds. It was an amazing outpouring of love and support that gave Bob what he needed to get through.

Farewell Party

Pete Seeger and Bob Gibson 1995

Bob and Pete reconnected at the Folk Alliance Conference which was held in Portland, Oregon in 1995.

Gibson clan gathered in 1995

(Back) Rose, Bob, Susan (Middle) Pati, Meridian, Pati’s son Jordon, Seannie holding Fergus, Stephen (Front) Pati’s daughter Mackenzie, Sarah

In A Family Way

In the years before he died, perhaps because he had more time with Sarah as a very young child, Bob got what he had missed with his first kids. He realized just how precious that was and what a trip it is to hang out with your kids and have a relationship with them. He’d started to work out relationships with his adult children, but he didn’t get stick around long enough to have a relationship Sarah as an adult.

Meridian Green

You’re Invited!

It was time for Bob to throw one last party. He envisioned a good old-fashioned Irish wake with his song Farewell Party, which he had recorded on Funky in the Country, as the theme.

The invitation said, “As my health has declined I have found I may miss music more than anything else. I miss making music, listening to music and being around people who have music in their blood. So, I’m going to throw a party and invite everyone to bring their voices, instruments and songs. I won’t be able to play or sing with you, but I really looking forward to being an audience of one.”

Last Hootenanny – His Own Wake

“One week before he died, Bob Gibson hosted his last hootenanny. He flew in from Portland, Oregon, with his wheelchair and his fulltime caregiver, and attended his own wake.”

Roger Ebert (who attended the party), Chicago Sun Times.

Some Last Words From Bob

“I’ve gone a lot of places and been with a lot of people and done a lot of different things. I rest pretty easy, no matter where I am now. I’m grateful that I have done so much and my life has been such an adventure. The lows have been as low as they can get and the highs have been as high as they can get. There were times when I perceived life as absolute hell and times I perceived it as heaven.

It’s been glorious. It’s been intense. I’ve never been much for ‘sipping’ life. I take gulps. For that reason I’ve liked it even when I didn’t like it. There were some gulps of some stuff I didn’t care for, but they really weren’t handed me by fate. I have dealt with incredible obstacles, all of which were self-inflicted. They might have been awful, but they weren’t hopeless and they weren’t unchangeable.

There is something working on me now called peace of mind. At one time I thought that concept was as square as it could be.”

He Made The Very Air Sparkle

He was a master of pleasure in the present with an amazing capacity to connect crowds of people with their own joy. Bob Gibson could turn any group into a celebration, an extraordinary event, a party where everyone is witty and beautiful, all the jokes are funny and the songs are all well-sung. There was a surge of electricity, a shot of adrenaline, a charged atmosphere; whatever that thing was that he brought to performances that made the very air sparkle, it was unique.

I love my father’s music. He made great music, and I’m grateful for all the recordings. But what I miss most is the rush of being in the room with him when he’d turn the magic on.

Meridian Green

Carole Bender

Truly one can see the impact Bob had by the stellar array of friends eager to talk about him including Pete

Seeger, Joan Baez, Peter Yarrow, Tom Paxton, Glenn Yarbrough, Hamilton Camp, Gordon Lightfoot, Roger McGuinn, Shel Silverstein and Studs Terkel, to mention just a few. As Gordon Lightfoot said, “Bob Gibson. You know, when I look back, it’s him and it’s Dylan — and that’s about as far as it goes! Truly an amazing person.”

As for my own personal involvement with Bob Gibson, I was a latecomer. When I was a young, idealistic folksinger myself, on the campus of Oklahoma State University in the early ’70s, my idols were

Tom Paxton and Gordon Lightfoot. Little did I know then that all of their works and performances had their roots in the works and performances of Bob Gibson.

Once introduced to his music, I became obsessed. I wanted to hear all the Bob Gibson recordings, only to find they were mostly unavailable. I wanted to learn more about this man, only to find there was very little information in print about him other than tributes by fellow performers. Finally I wanted to find him so I could see him perform, only to find to my extreme dismay that he was no longer able to. Still unwilling to give up, I set out on a personal odyssey to meet this giant of folk music and offer to help him tell his story.

The story of Bob Gibson is complex and not an easy one to tell. There are two distinct sides to the Gibson personality. There is the musical genius and there is the personal side. There is the energetic, enthusiastic young man who chose to set off with his banjo and share his love of music, countered by the performer who turned down virtually every opportunity to become one of folk music’s biggest stars.There is the bright, sparkling, charming stage personality contrasted by the man, also known as the “biggest womanizer in folk music,” who left a family in the shadows to grow up without him. There is the virtuoso banjo player and 12-string guitarist, countered by the man who sunk to the depths of drug addiction. In putting together the story of Bob Gibson, one is left with almost more questions than answers. His music survives to stir the soul. One day the personal life of Bob Gibson will be told as a fascinating story, perhaps a novel.

There was a part of this man that made him great. This is the part of his personality I choose to talk about. Even those who experienced the lowest times with Bob seem to recognize that he was special in

some way. The Bob Gibson I first came to know and the one to whom I longed to pay tribute is the one who gave the world a gift of his music. He left us all a wonderful gift. If he had a troubled personal life, it doesn’t alter that gift. He presented us with ourselves in song.

For that gift I choose to pay him homage.

I come before you with no claims of being the world’s foremost authority on either Bob Gibson or folk music history. I come simply as someone who cared enough to assemble the parts of a story that longed to be told.

If you will listen, I’m sure you will hear America singing.

Carole Bender, co-author extraordinaire of Bob Gibson | I Come For To Sing